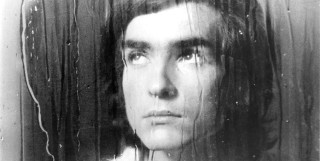

Mouchette (1967) tells the heart-wrenching story of a young girl tragically forced to grow up too soon. With a dying mother, alcoholic father, and a baby brother to take care of, Mouchette (Nadine Nortier), a mere teenager, is trapped in a life of responsibility for which she is — understandably — not yet mature enough for. Her painstaking alienation, self-denial, self-hatred, and occurent desperation for freedom is a powerful expression of a humanist integrity. As humans, we each may experience — at times — the desperation and yearning for child-like wonder that Mouchette constantly feels. For its empathetic nature and emotional resonance, Mouchette may be the most endearing, yet powerful of Bresson’s work.

To me, there is a point in one’s life where one becomes acutely aware of their own consciousness. In other words, one becomes conscious of their own volition — of their own freedom. Ironicaly, with this awareness comes the loss of true freedom. As the late hip hop artist Eyedea states in the song Infrared Roses, “the second you’re smart enough to recognize freedom, you’re no longer free”.

While reality itself necessarily tends our lives in this direction, this shift in consciousness occurs earlier in some people’s lives than others. It seems to accompany a need for the individual to “grow-up”. While some may experience this transformation naturally over a period of time, events such as a trauma, economical or emotional hardship, and external pressures or responsibilities can cause it to be forced upon people; in cases, it can be forced upon someone too young to know how to deal with it.

In Mouchette, our young, tragic figure is but a little girl. Her mother is dying, and she is forced to take care of both her and the baby. Her father could help, but is never around and uses his earnings to support his alcoholism. This is not the life of a thirteen (ish) year old girl. She watches as her classmates happily play together — not a care in the world; she throws clumps of mud at them, because she doesn’t know how to direct her feelings; her troubled life alienates her, and she feels the need to relate to someone.

She recognizes that the huntsman, Arsène (Jean-Claude Guilbert), is similarly alienated by the townspeople, and feels that she may relate with him. His ‘lone-ranger’ type figure intrigues her to follow him into the forest. When told that Arsène may have killed someone, Mouchette pledges to do what she can to help him. Her desire to help him reflects a true desire to help herself.

When Arsène forces himself upon her, she at first resists — for this reason, many claim what happens is rape, but I don’t think it’s quite so cut-and-dry. In one of Bresson’s most powerful moments, her arms stop flailing, and her hands clasp around him. This image represents the struggle she is experiencing. Though teetering the brink between childhood and adulthood, and fervently fighting off this transformation, her embracing of Arsène illustrates her final submission — she is no longer a child.

Near the end, a particular image conjures up Mouchette’s experience: a shot rabbit desperately fights to stand up, but, in the end, it is not able to. Likewise, despite all Mouchette’s attempts, she cannot prevent what is happening to her. The rabbit will die, and Mouchette will completely lose her freedom.

The final scene is amongst the most powerful in Bresson’s filmography. Mouchette whimsically rolls down a hill, a bed of flowers stopping her from falling into the lake. On her third tumble, she falls in and does not surface. This act is most commonly regarded as a tragic suicide, but I don’t believe it necessarily means that. The dream-like nature of this scene — it’s quaintness and her whimsy — makes me not take it quite so literally.

Understanding Bresson’s filmic nature — the clarity of his stories, but also their poetic tendencies — suggests that, whether she dies or not, this final image is a metaphor for loss of self. It may or may not be the end of her life, but, in any event, it truly is the end of Mouchette, the thirteen year-old girl who grew up too quickly.

10/10

Great review!

That’s an interesting idea about once you’re conscious of your own freedom, it is lost. Is that a philosophical theory or argument about freedom? I’d be curious to read more about that, if you have any links or if its easy to elaborate (I’m guessing not, it’s a topic that could be discusses for millennia, I’m sure). To me freedom is linked tightly with the idea of free will, one that is only an illusion in my opinion, and Bresson resonates with me in that regard. His characters don’t seem to have much freedom and are pushed through life by fate or chance, I find that very interesting.

I’ll mention though that I feel like I’m living my own life as if I do have a lot of freedom and control over it, but sometimes you just have to wonder whether that’s really true or just an illusion.

I didn’t consider the possibility that she lives or dies at the end, but I do agree that it’s irrelevant. She surely loses a part of her, if not her entire self, in that moment, and I thought it was very tragic to see that she was determined to reach that end by rolling down the hill 3 times. The end of the film was heartbreaking for me.

One thing I didn’t understand though, was why was she so against being helped? She refused the gift from the old lady at the end, who from my memory was the only person in the film not to have abused or insulted her in some way. My feelings were that she didn’t like others to pity her or that she’s untrustworthy of people’s intentions and didn’t recognize that she was being helped. What are your thoughts about that?

It’s considered by a lot of philosophers, particularly existentialists like Nietzsche, Sartre, and Camus. My theory on it is that once you are aware of your own consciousness, once your thoughts are intentional, and you become capable of choosing what to think about, freedom is lost. Freedom comes from new experience, where your thoughts are not controlled, but occur naturally as the result of experience. The way a child wonders about things. It’s a bit ironic, but I believe that having ‘your own thoughts’ is exactly what prevents freedom. By giving us the ‘freedom to act’, it limits us, thereby taking away any semblance of freedom we once had. Of course, I believe that freedom is attainable in adulthood, but it occurs only in fleeting moments when we are not thinking intentionally, but when we simply experience. New experiences, new places, new people in our lives give us more freedom.

Her refusal to be helped by people is not clear, but I believe it’s because she asserts her own independence. Part of why she is losing her freedom is because she feels obligated to be responsible. I remember being a teenager and thinking I was so smart and independent that I would take offense when someone would try to help me. “I can do it myself!” I think that’s the kind of thing she’s got going on. Untrustworthy of people’s intentions? This is probably a part of it as well. She’s been hurt by too many people — basically everyone in her life — to be easily willing to let anybody in.

That’s an interesting theory. I’m gonna have to read some more about it – I like philosophy but I can’t say I’ve studied it (I’m yet to find a philosophy text that’s fun to read).

That makes sense about asserting her independence, although she’s obviously immature about it, just like most of us at that age when we refuse help even if we desperately need it.